Square Root of negative one (√-1)

This basic recap of the types of numbers that exist in mathematics is provided as a foundation for a clearer understanding into the nature of √-1, imaginary numbers, and complex numbers,

Natural numbers: The counting numbers [1, 2, 3, ...] are commonly called natural numbers; however, other definitions include 0, so that the non-negative integers [0, 1, 2, 3, ...] are also called natural numbers. Natural numbers including 0 are also called whole numbers.

Integers: The positive and negative counting numbers, as well as zero, are defined as integers [..., −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...].

Rational numbers: Numbers that can be expressed as a ratio of an integer to a non-zero integer are known as rational numbers. All integers are rational, but the converse is not true; there are rational numbers that are not integers. [Examples or rational numbers: -¾ or ½]

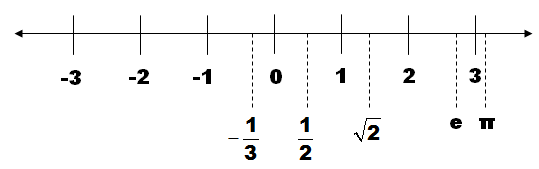

Real numbers: Numbers that can represent a distance along a line are considered real numbers. They can be positive, negative, or zero. All rational numbers are real, but the converse is not true. [Examples of real numbers: -2.58 or 4.1037]

Irrational numbers: Real numbers that are not rational. [Examples of irrational numbers: π or √2]

Real Number Line showing examples of integers, rational & irrational numbers.

Imaginary numbers: Numbers that equal the product of a real number and the square root of −1. The number 0 is both real and imaginary. In mathematics, √-1 is designated by the symbol i.

Complex numbers: Includes real numbers, imaginary numbers, and sums and differences of real and imaginary numbers. A complex number c is typically written in the following format: c = a + bi , where a is the real number portion and bi is the imaginary number part of the complex number.

The Complex Number Plane is created by the real numbers that lie along the horizontal axis and the imaginary numbers along the vertical axis.

The very first mention of people trying to use imaginary numbers dates all the way back to the 1st century. In 50 A.D., Heron of Alexandria studied the volume of an impossible section of a pyramid. What made it impossible was when he had to take √81-114. However, he deemed this impossible, and soon gave up. For a very long time, no one tried to manipulate imaginary numbers. Although, it wasn’t for a lack of trying. Once negative numbers were “invented”, mathematicians tried to find a number that, when squared, could equal a negative one. Not finding an answer, they gave up. In the 1500’s, some speculation about square roots of negative numbers was brought back. Formulas for solving 3rd and 4th degree polynomial equations were discovered, and people realized that some work with square roots of negative numbers would occasionally be required. Naturally, they didn’t want to work with that, so they usually didn’t. Finally, in 1545, the first major work with imaginary numbers occurred.

In 1545, Girolamo Cardano wrote a book titled Ars Magna. He solved the equation

x(10-x)=40, finding the answer to be 5 plus or minus √-15. Although he found that this was the answer, he greatly disliked imaginary numbers. He said that work with them would be, “as subtle as it would be useless”, and referred to working with them as “mental torture.” For a while, most people agreed with him. Later, in 1637, Rene Descartes came up with the standard form for complex numbers, which is a+bi. However, he didn’t like complex numbers either. He assumed that if they were involved, you couldn’t solve the problem. Lastly, he came up with the term “imaginary”, although he meant it to be negative. Issac Newton agreed with Descartes, and Albert Girad even went as far as to call these, “solutions impossible”. Although these people didn’t enjoy the thought of imaginary numbers, they couldn’t stop other mathematicians from believing that i might exist.

Rafael Bombelli was a firm believer in complex numbers. He helped introduce them, but since he didn’t really know what to do with them, he mostly wasn’t believed. He did understand that i times i should equal -1, and that –i times i should equal one. Most people did not believe this fact either. Lastly, he did have what people called a “wild idea”- the idea that you could use imaginary numbers to get the real answers. Today, this is known as conjugation. Although Bombelli himself did not have much of an impact at the time, he helped lead the way for imaginary numbers.

Over decades, many people believed that complex numbers existed, and set out to make them understood and accepted. One of the ways they wanted to make them accepted was to be able to plot them of a graph. In this case, the X-axis is would be real numbers, and the Y-axis would be imaginary numbers. If the number were purely imaginary (like 2i), it would just be on the Y-axis. If the number was purely real, it would just be on the X-axis. The first person who considered this kind of graph was John Wallis. In 1685, he said that a complex number was just a point on a plane, but he was ignored. More than a century later, Caspar Wessel published a paper showing how to represent complex numbers in a plane, but was also ignored. In 1777, Euler made the symbol i stand for √-1, which made it a little easier to understand. In 1804, Abbe Buee thought about John Wallis’s idea about graphing imaginary numbers, and agreed with him. In 1806, Jean Robert Argand wrote how to plot them in a plane, and today the plane is called the Argand diagram. In 1831, Carl Friedrich Gauss made Argand’s idea popular, and introduced it to many people. In addition, Gauss took Descartes’ a+bi notation, and called this a complex number. It took all these people working together to get the world, for the most part, to accept complex numbers.

Mathematicians kept working to make sure that imaginary and complex numbers were understood. In 1833, William Rowan Hamilton expressed complex numbers as pairs of real numbers (such as 4+3i being expresses as (4,3)), making them less confusing and even more believable. After this, many people, such as Karl Weierstrass, Hermann Schwarz, Richard Dedekind, Otto Holder, Henri Poincare, Eduard Study, and Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet all studied the general theory of complex numbers. Augustin Louis Cauchy and Niels Henrik Able made a general theory about complex numbers accepted. August Mobius made many notes about how to apply complex numbers in geometry. All of these mathematicians helped the world better understand complex numbers, and how they are useful.

Clearly, complex numbers are amazing. They have many uses, more than we realize. They have a fascinating history, full of some mathematicians not believing in them and others desperately trying to prove their existence. i is also fascinating, being the only imaginary number. Many mathematicians brought together as much proof as they could that imaginary numbers should exist, and we have them to thank today that we can use i whenever we please, without being questioned about it.

Closing Commentary by Michael Pierre Price: Chaos theory and fractals are important elements in helping me create much of my Algorithmic Expressionist art. Complex numbers are central to the mathematics I utilize, such as in the famous Mandelbrot fractal equation. As an artist, having a background in mathematics not only helps me have a much deeper appreciation for the work I create, but it has also been foundational in developing my signature abstract art.

The early stages of creating algorithmic expressionist art within my virtual art studio.